Commusings: My Origin Story as Glucose Goddess by Jessie Inchauspé

May 20, 2023

Dear Commune Community,

My car has a dashboard, one that I would never drive without. Why would I take my body out for a spin without the same transparency? So, 18 months ago, I applied a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) to my triceps. A CGM operates as a dashboard into the vehicle of my organism.

As a 20-year veteran of “the wellness industry,” I expected a good result when I opened the app that reports my blood glucose levels and was shocked to see the equivalent of the “check engine” light blinking. I was running fasting glucose levels of 125 mg/dl. Post-prandially, I was spiking to 200 and north.

Like approximately 50% of Americans, I had pre-diabetic blood glucose. And like 90% of pre-diabetics, I didn’t know it.

This simple device gave me insight into one of my most important biomarkers, and with that data came agency. I could observe what foods and situations would cause my levels to spike and what protocols lowered levels and evened out naturally occurring ups and downs. We want our blood glucose readings to resemble the rolling hills of Georgia, not the Swiss Alps. I adopted a low-glycemic diet, an intermittent fasting protocol and started deliberate cold water therapy, and, after 4 months, I brought my fasting glucose levels down 40 mg!

No one has done more to democratize knowledge about glucose than today’s essayist, Jessie Inchauspé (aka The Glucose Goddess). She possesses a unique combination of scientific knowledge and communication savvy that is helping millions of people manage their metabolic health. Commune is thrilled to be launching a course with her later this summer. You can sign up early for a free course pass here.

Here at jeffk@onecommune.com and avoiding sweets on IG @jeffkrasno.

In love, include me,

Jeff

My Origin Story as Glucose Goddess by Jessie Inchauspé

Excerpted from Glucose Revolution: The Life-Changing Power of Balancing Your Blood Sugar

What was the last thing you ate? Go on, think about it for a second.

Did you like it? What did it taste like? Where were you when you ate it? Who were you with? And why did you pick it?

Food is not only delicious, it is vital.

So now for the harder questions: Do you know how many grams of fat it has? Do you know if it will cause you to wake up with a pimple tomorrow? Do you know how much plaque it built up in your arteries or how many wrinkles it deepened on your face? Do you know if it’s the reason you’ll be hungry again in two hours, sleep poorly tonight, or feel sluggish tomorrow?

In short—do you know what the last thing you ate did to your body and mind?

Many of us don’t. I certainly didn’t before I started learning about a molecule called glucose.

“The animal tends to eat with his stomach, and the man with his brain,” wrote the philosopher Alan Watts. We often decide what to have for lunch based on what we read or hear, rather than based on what our bodies truly need. If only our bodies could speak to us, it would be a different story.

Well, I’ve got a scoop for you. As it turns out, our bodies speak to us all the time. We just don’t know how to listen.

This is where I blame our environment. Our nutritional choices are influenced by billion-dollar marketing campaigns aimed at making money for the food industry—campaigns for soda, fast food, and candy. These are usually justified under the guise of “what matters is how much you eat—processed foods and sugar aren’t inherently bad.” But science is demonstrating the opposite: processed foods and sugar are inherently bad for us, even if we don’t eat them in caloric excess.

Scientists have been studying how food affects us for a long time, but some particularly exciting discoveries have happened in the past five years in labs around the world: they’ve revealed our body’s reaction to food in real time—and have proven that although what we eat matters, how we eat it—in which order, combination, and grouping—matters, too.

Science shows us that there is one metric that affects all systems. If we understand this one metric and make choices to optimize it, we can greatly improve our physical and mental well-being.

This metric is the amount of blood sugar, or glucose, in our blood.

Glucose is our body’s main source of energy. We get most of it from the food we eat, and it’s then carried in our bloodstream to our cells. Its concentration can fluctuate greatly throughout the day, and sharp increases in concentration—glucose spikes—affect everything from our mood, our sleep, our weight, and our skin to the health of our immune system, our risk for heart disease, and our chance of conception.

You will rarely hear glucose discussed unless you have diabetes, but glucose actually affects each and every one of us. In the last few years, the tools to monitor this molecule have become more readily available. That, in combination with the advancements in science I mentioned above, means that we have access to more data than ever before—and we can use that data to gain insight into our bodies.

How I Got Here

You know the saying “Don’t take your health for granted”? Well, I did, until an accident at 19 changed my life.

I was in Hawaii on vacation with friends. One afternoon we went for a hike in the jungle, and we decided that jumping off a waterfall would be a great idea (spoiler alert: it was not).

My friends told me what to do: “Keep your legs really straight so that your feet go into the water first.”

“Got it!” I said, and off I went.

I forgot that advice as soon as I leapt off the edge of the cliff. I did not land feet first—I landed butt first. The pressure from the water created a shock wave up my spine, and, like dominos falling, each of my vertebrae compressed.

Shack-shack-shack-shack-shack-shack-shack, they went—all the way up to my second thoracic vertebra, which exploded into fourteen pieces under the pressure.

My life exploded into pieces, too. After that, I divided it in two:

before the accident

and after the accident.

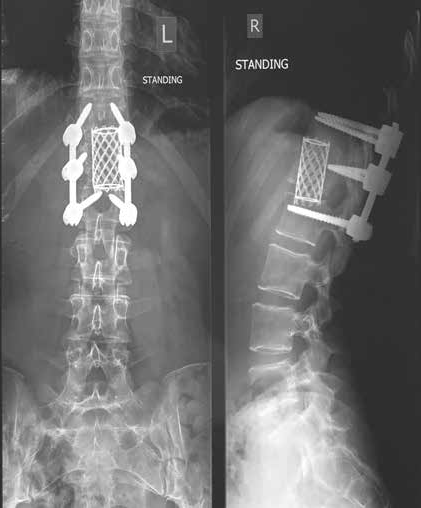

I spent the next two weeks immobilized in a hospital bed, waiting to undergo spinal surgery. As I lay awake, I kept mentally picturing what was going to happen, unable to fully believe it: the surgeon was going to open my torso from the side, at my waist, then from the back, at the level of the broken vertebra. He was going to take out the bone fragments as well as the two surrounding disks, then fuse three vertebrae together and drill six three-inch metal rods into my spine. With an electric drill.

The finished result. (No, I don’t set off the alarm at airport security, and

yes, this stays in forever.)

The day of the surgery arrived. As the anesthesiologist began putting me under for the eight-hour procedure, I wondered if she would be the last person I ever saw. If I could wake up on the other side of this, I knew I would be filled with gratitude for the rest of my life.

• • •

I woke up. It was the middle of the night, and I was alone in a recovery room. At first, I felt immense relief: I was alive. Then I felt pain. Correction: I felt a lot of pain. The new hardware was like an iron fist squeezing my spine. It was a dismal way to be greeted back into the world.

It’s true, I was filled with gratitude: deep, profound gratitude to be alive. But I was also in agony.

My body healed in a matter of months, but then my mind and soul were the ones that needed rehab. I felt disconnected from reality. Something was wrong. But I didn’t know what.

Unfortunately, no one else did, either. From the outside I seemed well again.

I was living in London at the time, and I remember sitting in the Tube, looking at the commuters opposite me, wondering how many of them were also going through something difficult and hiding it, just like I was.

It became abundantly clear to me that it’s hard to know what is going on inside our bodies.

And that was how, four years later, I ended up on the train headed thirty-nine miles south of San Francisco, to an office in Mountain View. Having decided to figure out how to communicate with my body, I felt that I needed to work at the forefront of health technology. In 2015, that forefront was genetics.

I had landed an internship at the startup 23andMe (so named because we all have twenty-three pairs of chromosomes that carry our genetic code).

My thinking went like this: My DNA created my body, so if I can understand my DNA, I can understand my body.

I grew close to the other scientists on the research team, then read through all the papers they had published and started asking questions. But to my disappointment, little by little, it became clear to me that DNA wasn’t as predictive as I had thought. For instance, your genes can increase your likelihood of developing type 2 diabetes, but they can’t tell you for sure whether you’ll get it. Looking at your DNA can only give you a sense of what might happen. For most chronic conditions, from migraines to heart disease, the cause ends up being much more attributable to “lifestyle factors” than to genetics.

In short, your genes don’t determine how you feel when you wake up in the morning.

In 2018, 23andMe launched a new initiative. It was led by the Health Research & Development team, which was in charge of coming up with cutting-edge ideas. They were discussing . . . continuous glucose monitors.

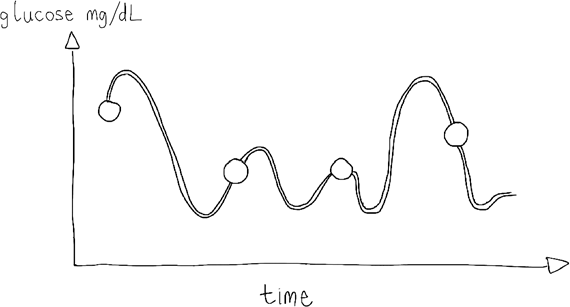

Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) are small devices worn on the back of your arm that track glucose levels. They were created to replace the finger pricks that people with diabetes have been using for decades and that give glucose measurements only a few times a day. With a CGM, glucose levels are measured every few minutes.

Continuous glucose monitors, or CGMs (the line), capture glucose curves that traditional finger prick tests (white circles) miss.

Now entire glucose curves are revealed and conveniently sent to your smartphone. It was a real game changer for people with diabetes, who rely on glucose measurements to dose their medication.

When the Health Research & Development team announced a new study looking into food response in nondiabetics, I immediately asked to be a part of it. I was always on the lookout for something that could help me understand my own body. But I definitely did not expect what came of it.

With my phone handy, I could check my glucose levels at any time.* The numbers showed me how my body responded to what I ate (or didn’t) and how I moved (or didn’t). I was getting messages from the inside. Well, hello there, body!

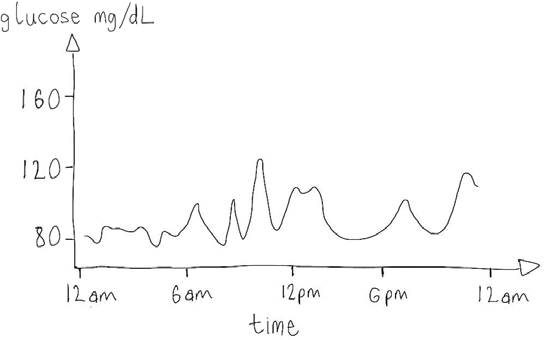

A day’s glucose data, right off the continuous glucose monitor.

I ran my own experiments and took note of everything. My lab was my kitchen, my test subject was myself, and my hypothesis was that food and movement influence glucose through a set of rules that we could define.

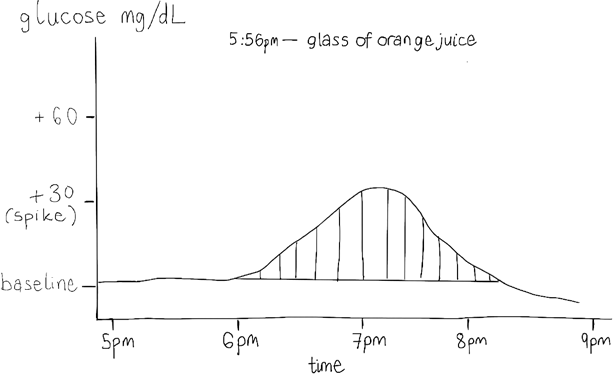

Zoomed into the four hours surrounding the time I drank orange juice, 5:56 p.m.

Quite quickly, I started noticing strange patterns: Nachos on Monday, big spike. Nachos on Sunday, no spike. Beer, spike. Wine, no spike. M&Ms after lunch, no spike. M&Ms before dinner, spike.

Tired in the afternoon: glucose had been high at lunch. Lots of energy all day: glucose was very steady.

Big night out with friends: glucose roller coaster through the night.

Stressful presentation at work: spike. Meditation: steady. Cappuccino when I was rested: no spike. Cappuccino when I was tired: spike.

Bread: spike. Bread and butter: no spike.

Things got even more interesting as I linked my mental states to my glucose levels. My brain fog (which I had started experiencing since my accident) often correlated with a big spike, sleepiness with a big dip. Cravings correlated with a glucose roller coaster. When I woke up feeling groggy, my glucose levels had been high throughout the night.

I sifted through the data, reran many experiments, and checked my hypothesis against published studies. To feel my best, it became clear that I had to avoid big spikes and dips in my glucose levels. And that was what I did: I learned how to flatten my glucose curves

I was making transformative discoveries about my health. I cured my brain fog and curbed my cravings. When I woke up, I felt amazing. For the first time since my accident, I began to feel truly well again.

So I started telling my friends about it, and that’s how the Glucose Goddess movement began.

* Technically not in my blood but in the fluid between my cells. These are tightly correlated.

Jessie Inchauspé is a French biochemist and author. She is on a mission to translate cutting-edge science into easy tips to help people improve their physical and mental health. In her first book, Glucose Revolution, a #1 international bestseller translated into 41 languages, she shared her startling discovery about the essential role of blood sugar in every aspect of our lives, and the surprising hacks to optimize it. Jessie is the founder of the wildly popular Instagram account @GlucoseGoddess, where she teaches over one million people about transformative food habits. She holds a BSc in mathematics from King’s College, London, and an MSc in biochemistry from Georgetown University.

Excerpted from The Glucose Goddess Method. Copyright © 2023, Jessie Inchauspé. Reproduced by permission of Simon Element, an imprint of Simon & Schuster. All rights reserved.

Leading teachers, life-changing courses...

Your path to a happier, healthier life

Get access to our library of over 100 courses on health and nutrition, spirituality, creativity, breathwork and meditation, relationships, personal growth, sustainability, social impact and leadership.

Stay connected with Commune

Receive our weekly Commusings newsletter + free course announcements!